Collaboration is the latest rallying cry of software vendors hoping to embed new generations of enterprise class tools and user experiences into the fabric of the modern workplace. Microsoft, IBM, and other firms expect that control or leadership in the market for collaboration, whether by owning the architecture, systems, or other solution components, will be lucrative. A recent Radicati Group study (quality unconfirmed…) of the market size for enterprise collaboration offered an estimate of $1.6 billion now, growing 10% annually to $2.3 billion in 2010.

Beyond the substantial money to be made creating, selling, installing, and servicing collaboration solutions lies the strategic advantage of market definition. The vendor(s) that own(s) the collaboration space expect(s) to become an integral to the knowledge economy’s supporting environment in the same way that Ford and General Motors became essential to the suburbanized consumer architectures of the post WWII era by serving simultaneously as employers, manufacturers, cultural marketers, capital reservoirs, and automobile sellers. Collaboration vendors know that achieving any level of indispensibility will enhance their longevity by making them a necessity within the knowledge economy.

It’s worth taking a moment to call attention to the implications: by defining the user experiences and technological building blocks brought together to realize collaboration in large enterprises, these vendors will directly shape our basic concepts and understanding (our mental models and cognitive frames) of collaboration. Once embedded, these architectures, systems, and business processes, and the social structures and conceptual models created in response, will in large part define the (information) working environments of the future.And yes, this is exactly what these vendors aspire to achieve; the Microsoft Sharepoint Products and Technologies Development Team blog, offers:

“SharePoint Products and Technologies have become a key part of our strategy for delivering a complete working environment for information workers, where they can collaborate together, share information with others, and find information and people that can help them solve their business problems.“

[From SHAREPOINT’S ROLE IN MICROSOFT’S COLLABORATION STRATEGY.]

And IBM’s marketing is not pitched and delivered in a manner as sweeping, but the implications are similar, as in the overview IBM® Workplace™: Simply a better way]:

“IBM Workplace™ Solutions are role-based frameworks to help customers apply IBM Workplace technologies faster and more productively… These solutions are designed to provide ‘short-cuts’ for creating a high performance role-based work environment, helping to accelerate time-to-value.“

The Models for communication and relationships built into our tools are very powerful, and often employed in other spheres of life. How many times have you started writing a birthday card for a friend, and found yourself instinctively composing a set of bullet points listing this person’s chief virtues, notable character traits, and the most important / amusing moments of your friendship. The creeping ubiquity of the rhetorical style of Powerpoint (Tufte’s essay here) is just one example of the tremendous social impact of a habituated model of communicative practices that’s run amok.

What does the future hold, in terms of enterprise vendor control over everyday working experiences? I’ve written before on the idea that the days of the monolithic enterprise systems are numbered, making the point along the way that these behemoths are the result of a top-down, one-size-for-all approach. I think the same is true of the current approach to collaboration solutions and working environments. And so I was happy to see Andrew McAfee of Harvard Business School make several strong points about how enterprise collaboration efforts will realize greater success by *reducing* the amount of structure imposed on their major elements — roles, workflows, artifacts, and relationships — in advance of actual use.

McAfee sees considerable benefit in new approaches to enterprise IT investment and management that reduce the top-down and imposed nature of enterprise environments and solutions, in favor of emergent structures created by the people who must work successfully within them. McAfee advocates allowing staff to create the identities, structures and patterns that will organize and govern their collaboration environments as necessary, in an emergent fashion, instead of fixing these aspects long before users begin to collaborate.

McAfee says:

“When I look at a lot of corporate collaboration technologies after spending time at Wikipedia, del.icio.us, Flickr, and Blogger I am struck by how regimented, inflexible, and limited the corporate stuff seems, because it does some or all of the following:

- Gives users identities before they start using the technology. These identities assign them certain roles, privileges, and access rights, and exclude them from others. These identities almost always also place them within the existing organizational structure and formal corporate hierarchy.

- Contains few truly blank pages. Instead, it has lots of templates–for meetings, for project tracking, for documents and reports, etc.

- Has tons of explicit or implicit workflow– seqences [sic] of tasks that must be executed in order.

How much of this structure is necessary? How much is valuable? Well, the clear success stories of Web 2.0 demonstrate that for at least some types of community and collaboration, none of it is.“

The critical question is then “what types of community and collaboration require which approaches to creating structure, and when?” As anyone who’s used a poorly or overly structured collaboration (or other enterprise) tool knows, the resulting environment is often analogous to a feudal society designed and managed by crypto-technical overlords; one in which most users feel as if they are serfs bound to the land for in perpetuity in order to support the leisure-time and war-making indulgences of a small class of shareholding nobility.

Answering these questions with confidence based on experience will likely take time in the range of years, and require numerous failed experiments. There’s a larger context to take into account: the struggle of enterprise software vendors to extend their reach and longevity by dominating the language of collaboration and the range of offerings is one part of a much broader effort by society to understand dramatic shifts in our ways of working, and the social structures that are both driven by and shape these new ways of working. And so there are several important ideas and questions underlying McAfee’s assessment that social system designers should understand.

One of the most important is that the notion of “collaboration” is conceptual shorthand for how you work, who you work with, and what you do. In other words, it’s a distillation of your professional identity. Your role in a collaboration environment defines who you are within that environment.

More importantly, from the perspective of growth and development, your system assigned role determines who you can *become*. Knowledge workers are valued for their skills, experience, professional networks, public reputations, and many other fluid, context dependent attributes. And so locking down their identities in advance strips them of a substantial proportion of their current value, and simultaneously reduces their ability to adapt, innovate, and respond to environmental changes by shifting their thinking or practices. In plain terms, determining their identities in advance precludes the creation of future value.

Another important underlying idea is the importance of properly understanding the value and utility of differing approaches to systematization in differing contexts. McAfee’s assessment of the unhealthy consequences of imposing too much structure in advance is useful for social system designers (such as information architects and knowledge managers), because it makes the outcomes of implicit design strategies and assumptions clear and tangible, in terms of the negative effects on the eventual users of the collaboration environment. For complex and evolving group settings like the modern enterprise, creating too much structure in advance points to a misplaced understanding of the value and role of design and architecture.

Fundamentally, it indicates an overestimation of the value of the activity of systematizing (designing) collaboration environments to high levels of detail, and without recognition for evolutionary dynamics. The design or structure of any collaboration environment — of any social system — is only valuable for how well it encourages relationships and activity which advance the goals of the organization and it’s members. The value of a designer in the effort to create a collaborative community lies in the ability to create designs that lead to effective collaboration, not in the number or specificity of the designs they produce, and especially not in the artifacts created during design — the templates, workflows, roles, and other McAfee mentioned above. To simplify the different views of what’s appropriate into two artificially segmented camps, the [older] view that results in the premature creation of too much structure validates the design of things / artifacts / static assemblies, whereas the newer view valuing minimal and emergent structures acknowledges the greater efficacy of designing dynamic systems / flows / frameworks.

The overly specific and rigid design of many collaboration system components coming from the older design viewpoint in fact says much about how large, complex enterprises choose to interpret their own characters, and create tools accordingly. Too often, a desire to achieve totality lies at the heart of this approach.

Of course, most totalities only make sense — exhibit coherence — when viewed from within, and when using the language and concepts of the totality itself. The result is that attempts to achieve totality of design for many complex contexts (like collaboration within enterprises large or small) represent a self-defeating approach. That the approach is self-defeating is generally ignored, because the pursuit of totality is a self-serving exercise in power validation, that benefits power holders by consuming resources potentially used for other purposes, for example, to undermine their power.

With the chimera of totality set in proper context, it’s possible to see how collaboration environments — at least in their most poorly conceived manifestations — will resemble virtual retreads of Taylorism, wherein the real accomplishment is to justify the effort and expense involved in creating the system by pointing at an excessive quantity of predetermined structure awaiting habitation and use by disenfranchised staff.

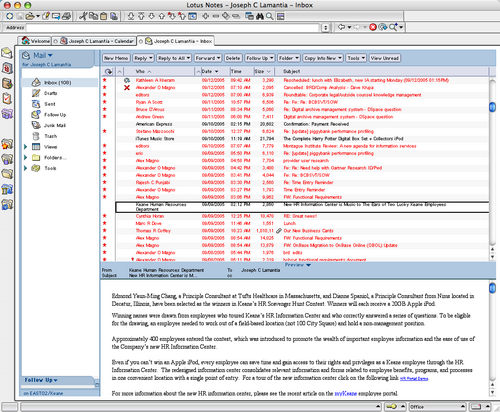

At present, I see two divergent and competing trends in the realm of enterprise solutions and user experiences. The first trend is toward homogeneity of the working environment with large amounts of structure imposed in advance, exemplified by comprehensive collaboration suites and architectures such as MSOffice / Sharepoint, or IBM’s Workplace.

The second trend is toward heterogeneity in the structures informing the working environment, visible as variable patterns and locuses of collaboration established by fluid groups that rely on adhoc assortment of tools from different sources (BaseCamp, GMail, social bookmarking services, RSS syndication of social media structures, communities of practice, business services from ASP providers, open source applications, etc.).

But this itself is a short term view, when situation within a longer term context is necessary. It is common for systems or environments of all sizes and complexities to oscillate cyclically from greater to lesser degrees of structure, along a continuüm ranging from homogeneous to heterogeneous. In the short term view then, the quest for totality equates to homogeneity, or even efforts at domination. In the long term view, however, the quest for totality could indicate an immature ecosystem that is not diverse, but may become so in time.

Applying two (potential) lessons from ecology — the value of diversity as an enhancer of overall resilience in systems, and the tendency of monocultures to exhibit high fragility — to McAfee’s points on emergence, as well as the continuüm view of shifting degress of homogeneity, should tell us that collaboration solution designers would be wise to do three things:

The end result should be an enterprise approach to collaboration that emphasizes the design of infrastructure for communities that create their own structures. Big vendors be wary of this enlightened point of view, unless you’re willing to respond in kind.