I believe the value of second generation clouds will be to offer ready navigation and access to deep, complex landscapes of meaning built up from the cumulative semantic information contained in many interconnected tag clouds. I’d like share some thoughts on this idea; I’ll split the discussion into two posts, because there’s a fair amount of material.

In a previous post on tag clouds, I suggested that the great value of first generation tag clouds is their ability to make concepts and metadata – semantic fields – broadly accessible and easy to understand and work with through visualization. I believe the shift in the balance of roles and value from first to second generation reflects natural growth in cloud usage and awareness, and builds on the two major trends of tag cloud evolution: enhanced visualization and functionality for working with clouds, and provision of extensive contextual information to accompany tag clouds.

Together, these two growth paths allow cloud consumers to follow the individual chains of understanding that intersect at connected clouds, and better achieve their goals within the information environment and outside. Fundamentally, I believe the key distinctions between first and second generation clouds will come from the way that clouds function simultaneously as visualizations and navigation mechanisms, and what they allow navigation of – landscapes of meaning that are rich in semantic content of high value.

For examples of both directions of tag cloud evolution coming together to support navigation of semantic landscapes, we can look at some of the new features del.icio.us has released in the past few months. I’ve collected three versions of the information architecture of the standard del.icio.us URL details page from the past seven months as an example of evolution happening right now.

The first version (screenshot and breakdown in Figure 1) shows the URL details page sometime before August 15th, 2005, when it appeared on Matt McAlister’s blog.

Figure 1: Del.icio.us URL Page – August 2005

The layout or information architecture is fairly simple, offering a list of the common tags for the url / focus, a summary of the posting history, and a more detailed listing of the posting history that lists the dates and taggers who bookmarked the item, as well as the tags used for bookmarking. There’s no cloud style visualization of the tags attached to this single focus available: at this time, del.icio.us offered a rendered tag cloud visualization at the aggregate level for the whole environment.

Environment and system designers know very well that as the scope and complexity of an environment increase – in this case, the number of taggers, focuses, and tags, plus their cumulative histories – it becomes more important for people to be explicitly aware of the context of any item in order to understand it properly. Explicit context becomes more important because they can rely less and less on implicit context or assumptions about context based on the universal aspects of the environment. This is how cloud consumers’ needs for clearly visible and accessible chains of understanding drives the features and capabilities of tag clouds. Later versions of this page addresses these needs in differing ways, with differing levels of success.

Figure 2 shows a more recent version of the del.licio.us history for the Ma.gnolia.com service. This screenshot taken about ten days ago in early March, while I was working on a draft of this post.

Figure 2: Del.icio.us URL Page – Early March 2006

Key changes from the first version in August to this second version include:

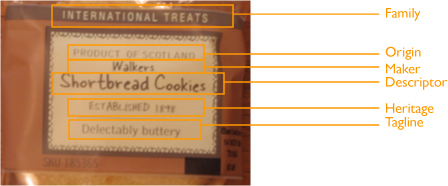

The most important change in this second version is the removal of the individual sets of tags from the Posting History. Separating the tags applied to the focus from associaton with the individual taggers that chose them strips them of an important layer of context. Removing the necessary context for the tag cloud breaks the chain of understanding (Figure 3) linking taggers and cloud consumers, and obscures or increases the costs of the social conceptual exchange that is the basic value of del.icio.us to its many users. In this version, cloud consumers consumers reading the URL details page can only find specific taggers based on the concepts they’ve matched with this focus by visiting or navigating to each individual taggers’ area within the larger del.icio.us environment one at a time.

Figure 3: Chain of Understanding

The switch to rendering the Common Tags block as a tag cloud is also important, as an indicator of the consistent spread of clouds to visualize semantic fields, and their growing role as navigation tools within the larger landscape.

The User Notes are a good example of an attempt to provide additional contextual information with (potentially) high value. User Notes are created by users exclusively for the purpose of providing context. The other forms of context shown in the new layout – the Posting History, Related Items – serve a contextual function, but are not created directly by users with this goal in mind. The difference between the two purposes for these items undoubtedly influences the way that people create them, and what they create: it’s a question that more detailed investigations of tagging practices will surely examine.

The third version of the same URL history page, shown in Figure 4, was released very shortly after the second, proving tag cloud evolution is happening so quickly as to be difficult to track deliberately on a broad scale.

Figure 4: Del.icio.us URL Page – March 2006 #2

This version changes the content and layout of the Posting History block, restoring the combined display of individual taggers who tagged the URL, with the tags they applied to it, in the order in which they tagged the URL for the first time.

The third version makes two marked improvements over the first and second versions:

These three different versions of the del.icio.us URL details page show that the amount and type of contextual information accompanying a single focus is increasing, and that the number of concrete navigable connections to the larger semantic landscape of which the focus is one element also increasing

Overall, it’s clear that clouds are quickly emerging as navigation tools for complex landscapes of meaning, and that cloud context has and will continue to become more important for cloud creation and use.

And so before discussing the context necesary for clouds and the role of clouds as navigation aids in more detail, it will be helpful to get an overview of landscapes of meaning, and how they arise.

Landscapes of Meaning

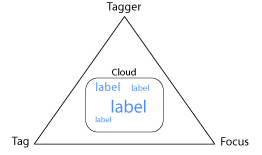

A landscape of meaning is a densely interconnected, highly valuable, extensive information environment rich in semantic content that is created by communities of taggers who build connected tag clouds. In the early landscapes of meaning emerging now, a connection between clouds can be a common tag, tagger, or focus: any one of the three legs of the Tagging Triangle required for a tag cloud (more on this below). Because tag clouds visualize semantic fields, connected tag clouds visualize and offer access to connected semantic fields, serving as bridges between the individual accumulations of meaning each cloud contains.

Connecting hundreds of thousands of individually created clouds and fields, as del.icio.us has enabled social bookmarkers to do by providing necessary tools and infrastructure, creates a very large information environment whose terrain or geography is composed of semantic information. Such a semantic landscape is a landscape constructed or made up of meaning. It is an information environment that allows people to share concepts or for social purposes of all kinds, while supported with visualization, contextual information, functionality, and far-ranging navigation capabilities.

The flickr Landscape

flickr is a good example of a landscape of meaning that we can understand as a semantic landscape. In a previous post on tag clouds, I considered the flickr all time most popular tags cloud (shown in Figure 5) in light of the basic structure of clouds:

“The flickr style tag cloud is …a visualization of many tag separate clouds aggregated together. …the flickr tag cloud is the visualization of the cumulative semantic field accreted around many different focuses, by many people. …the flickr tag cloud functions as a visualization of a semantic landscape built up from all associated concepts chosen from the combined perspectives of many separate taggers.”

Figure 5: The flickr All Time Most Popular Tags Cloud

From our earlier look at the structure of first generation tag clouds we know a tag cloud visualizes a semantic field made up of concepts referred to by labels which are applied as tags to a focus of some sort by taggers.

Based on our understanding of the structure of a tag cloud as having a single focus, the flickr cloud shows something different because it includes many focuses. The flickr all time most popular tags cloud combines all the individual tag clouds around all the individual photos in flickr into a single visualization, as Figure 6 shows.

Figure 6: The flickr Landscape of Meaning

This means the flickr all time most popular tags cloud is in fact a visualization of the combined semantic fields behind each of those individual clouds. It’s quite a bit bigger in scope than a traditional single focus cloud. Because the scope is so large, the amount of meaning it summarizes and conveys is tremendous. The all time most popular tags cloud is in fact a historic window on the current and historical state of the semantic landscape of flickr as a whole.

This is where context becomes critical to the proper understanding of a tag cloud. The cloud title “All time most popular tags” sets the context for this tag cloud, within the boundaries of the larger landscape environment defined and communicated by flickr’s user epxerience. Without this title, the cloud is meaningless despite the large and complex semantic landscape – all of the information environment of flickr – it visualizes so effectively, because cloud consumers cannot retrace a complete chain of understanding to correctly identify the cloud’s origin.

flickr – 1st Generation Landscape Navigation

The flickr cloud is a powerful navigation mechanism for quickly and easily moving about within the landscape of meaning built up by all those thousands and thousands of individual clouds. Still, because it is a first generation cloud, we cannot directly follow any of the many individual chains of understanding connecting this cloud’s tags back to specific taggers, or the concepts they associate with specific photos or focuses. In this visualization, the group’s understanding of meaning is more important than any individual’s understanding. And so the flickr cloud does not yet allow us comprehensive navigation of the underlying semantic landscape illustrated in Figure 6 (chains of understanding suggested in light green). The flickr cloud also remains a first generation tag cloud because users cannot control its context.

Figure 7: A Semantic Landscape

Even so, these navigational and contextual needs will help identify the way that users rely on clouds to work in landscapes of meaning.

Growth of Landscapes

Landscapes of meaning like flickr, del.icio.us, or the burgeoning number of social semantic business ventures debuting as I write – typically grow from the bottom up, emerging as dozens or thousands of individual tag clouds created for different reasons by different taggers coincidentally or deliberately interconnect and overlap, all of this happening through a variety of social mechanisms. Taggers typically create connected or overlapping tag clouds one at a time, adding tags, focuses, and taggers (by creating new accounts) in the ad hoc fashion of open networks and architectures. But first we should look at the Tagging Triangle to understand the most basic elements of a tag cloud.

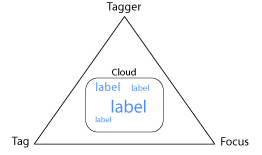

The Tagging Triangle

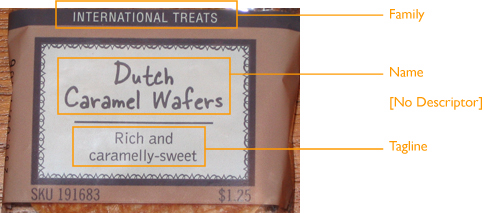

To make a tag cloud, you have to have three elements: a focus, a tagger, and a(t least one) tag. I call this the Tagging Triangle, illustrated in Figure 8. In the most common renderings of familiar tag clouds, one or two of these elements are often implied but not shown: yet all three are always present.

This illustration shows a cloud of labels, not tags, because a rendered cloud is really a list of labels. The labels shown in most first generation clouds are often tags, but structurally they could also be a set of names for taggers, as in the del.icio.us posting history block proto-cloud we saw above, or a set of focuses as in the ‘Inverted Cloud’ I suggested.

Figure 8: The Tagging Triangle

An Example Landscape

A simple example of the growth of semantic landscapes leads naturally to the discussion of specific ways that tag clouds will enable navigation within large landscapes of meaning.

Figure 9 shows the tag cloud accreted around a single focus. This cloud includes some of the tags that Tagger 1 has used in total across all the tag clouds she’s created (those other clouds aren’t shown). We’ll assume that she’s created other clouds for other focuses.

Figure 9: A Single Tag Cloud

When a second person, Tagger 2, tags that same focus (again with a subset of the total set of all his tags), and some of those tags are the same as those used for this focus by Tagger 1, their individual tag clouds for this focus (shown by the dashed line in the cumulative tag cloud) connect via the common tags, and the cumulative cloud grows. If any of the tags from their total sets are the same, but are not used for this focus, they form another connection between the two taggers. Figure 10 shows two individual clouds connected in both these ways.

Figure 10: Two Connected Clouds

When a third tagger adds a third cloud with common tags and unique tags around the same focus, the cumulative cloud grows, and the number of both kinds of connections between tags and taggers grows. Figure 11 shows three connected clouds.

Figure 11: Connected Clouds

Every tag cloud visualizes a semantic field, and so the result of this bottom up growth is a series of interlinked semantic fields centered around a common focus, as Figure 12 shows. Since semantic fields are made of concepts, linked fields result in linked concepts.

Figure 12: Connected Semantic Fields

The total number and the variety of kinds of interconnections amongst these three taggers, their tags, and a single focus is remarkable. As this simple example shows, the total number and density of connections linking even a moderate size population of taggers, tags, and focuses could quickly become very large. This increased scale drives qualitative and quantitative topology changes in the network that permit a landscape of meaning to emerge from connected semantic fields.

Landscapes And Depth

The accumulation of connections and concepts creates a landscape of meaning with real depth; but it’s the depth of a landscape that drives its value. For this discussion, I’m defining depth loosely as the amount of semantic information or the density of the semantic field either across the whole landscape, or at a chosen point.

Value of course is a very subjective judgement. In participatory economies like that of del.icio.us, the value to individual users is predominantly one of loosely structured semantic exchange based on accumulation of collective value through shared individual efforts. From a business viewpoint, a group of investors and yahoo as a buyer saw considerable value in the emergent landscape and / or other kinds of assets

To make the idea of depth a bit clearer, Figure 13 illustrates two views of a semantic landscape built up by the overlap of tag clouds. The aerial view shows the contents, distribution, and overlap of a number of tag clouds around a set of focuses. The horizon view shows the depth of the semantic field for each focus, based on the amount of overlap or connection between the cloud around that focus and all the other clouds.

Figure 13: Semantic Landscape Depth Views

Of course this is only a conceptual way of showing the cumulative semantic information that makes up a landscape of meaning, so it does not address the relative value of this information. Plainly some indication of the quality of the semantic information in a landscape is critical important to measurements of both depth and value. Metrics for quality could come from a combination of assessment of the diversity and granularity of the tag population for the focus, benchmarks for the domain of the focus and taggers (healthcare industry), and an estimate on the maturity of the domain, the focus, and the tag clouds in the semantic landscape.

Looking ahead, it’s likely that accepted metrics for defining and describing the depth, value, and characteristics of semantic fields and landscapes will emerge as new combinations of some of the measurements used now in the realms of cognitive linguistics, set theory, system theory, topology, information theory, and quite a few other disciplines besides.

In Part Two

The second post in this series of two will follow several of the topics introduced here to conclusion, as well as cover some new topics, including:

- How chains of understanding shape needs for cloud context and navigation paths

- How the tagging triangle will define navigation within landscapes of meaning

- The emergence of stratification in landscapes of meaning

- The idea that clouds and landscapes have a shape which conveys meaning and value

- The kinds of contextual information and controls necessary for navigation and social exchanges

Watching Navigation Follow Chains of Understanding

I’ll close with a screencast put together by Jon Udell that captures a wide ranging navigation path through the del.icio.us landscape.