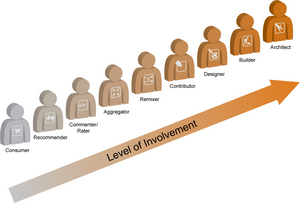

Common models for participation in social and contributory media invariably set ‘content creators’ – the group of people who provide original material – at the top of an implied or explicit scale of comparative value. Bradley Horowitz’s Content Production Pyramid is one example, Forrester’s Social Technographics Ladder is another. In these models, value – usually to potential marketers or advertisers external to the domain in question – is usually measured in terms of the level of involvement of the different groups present, whether consumers, synthesizers, or creators.

By the numbers, these models are accurate: the vast majority of the content in social media comes from a small slice of the population. And for businesses, content creators offer greater potential to commercialize / monetize / trade influence.

It’s time to evolve these models a bit, to better align them with the sweeping DIY cultural and technological shift happening offline in the real world, as well as online.

The DIY shift manifests in many ways:

The essential feature of the DIY shift is co-creation: the presence of many more people in *all aspects* of creation and production, whether of software, goods, ideas, etc. Co-creation encompasses more than straightforward on-line content creation – such as sharing a photo, or writing a blog post – acknowledged by the architecture of participation, user-generated content (and ugly term…), crowd-sourcing, and collective and contributory media models.

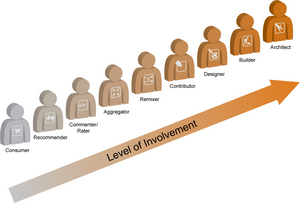

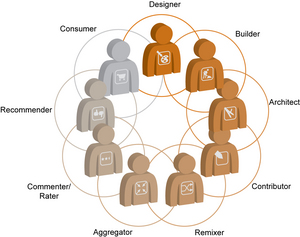

Co-creation includes active shaping of structure, pattern, rules, and mechanisms, that support simple content creation. This requires activity and involvement from roles we often label editor, builder, designer, or architect, depending on the context. The pyramid and ladder models either implicitly collapse these perspectives into the general category of ‘creator’, which obscures very important distinctions between them, or leaves them out entirely (I’m not sure which). It is possible to plot these more nuanced creative roles on the general continuum of ‘level of involvement’, and I often do this when I talk about the future of design in the DIY world.

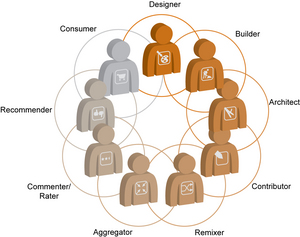

A better model for this world is the ecology of co-creation, which recognizes that the key difference between industrial production models and the DIY future is that the walls separating traditional creators from consumers have fallen, and all parties interconnect. Judgements of value in ecologies take on very different meanings: Consider the differing but all vitally important roles of producers, consumers, and decomposers in a living ecosystem.

What will an ecology of co-creation look like in practical / operational form? In The Bottom Is Not Enough, Kevin Kelly offers, “…now that crowd-sourcing and social webs are all the rage, it’s worth repeating: the bottom is not enough. You need a bit of top-down as well.”

An ecology of co-creation that combines top-down architecture and design with bottom-up contribution and participation will take the form of a deliberate hybrid.

I’ll quote Kelly again (at some length):

Here’s how I sum it up: The bottom-up hive mind will always take us much further than even seems possible. It keeps surprising us in this regard. Given enough time, dumb things can be smarter than we think.

At that same time, the bottom-up hive mind will never take us to our end goal. We are too impatient. So we add design and top down control to get where we want to go.

The systems we keep will be hybrid creations. They will have a strong rootstock of peer-to-peer generation, grafted below highly refined strains of controlling functions. Sturdy, robust foundations of user-made content and crowd-sourced innovation will feed very small slivers of leadership agility. Pure plays of 100% smart mobs or 100% smart elites will be rare.

The real art of business and organizations in the network economy will not be in harnessing the crowd of “everybody” (simple!) but in finding the appropriate hybrid mix of bottom and top for each niche, at the right time. The mix of control/no-control will shift as a system grows and matures.

[Side note: Metaphors for achieving the appropriate mix of control/no-control for a system will likely include choreographing, cultivating, tuning, conducting, and shepherding, in contrast to our current directive framings such as driving, directing, or managing.]

Knowledge at Wharton echoes Kelly, in their recent article The Experts vs. the Amateurs: A Tug of War over the Future of Media

A tug of war over the future of media may be brewing between so-called user-generated content — including amateurs who produce blogs, video and audio for public consumption — and professional journalists, movie makers and record labels, along with the deep-pocketed companies that back them. The likely outcome: a hybrid approach built around entirely new business models, say experts at Wharton.

No one has quite figured out what these new business models will look like, though experimentation is under way with many new ventures from startups and existing organizations.

The BBC is putting hybridization and tuning into effect now, albeit in limited ways that do not reflect a dramatic shift of business model.

In Value of citizen journalism Peter Horrocks writes:

Where the BBC is hosting debate we will want the information generated to be editorially valuable. Simply having sufficient resource to be able to moderate the volume of debate we now receive is an issue in itself.

And the fact that we are having to apply significant resource to a facility that is contributed regularly by only a small percentage of our audiences is something we have to bear in mind. Although of course a higher proportion read forums or benefit indirectly from how it feeds into our journalism. So we may have to loosen our grip and be less worried about the range of views expressed, with very clear labeling about the BBC’s editorial non-endorsement of such content. But there are obvious risks.

We need to be able to extract real editorial value from such contributions more easily. We are exploring as many technological solutions as we can for filtering the content, looking for intelligent software that can help journalists find the nuggets and ways in which the audience itself can help us to cope with the volume and sift it.

What does all this mean for design(ers)? Stay tuned for part two…