November 29th, 2007 — 12:00am

In a world that’s moving so fast it’s hard to keep track of when you are, let alone where, there’s a need for experiences that move at more relaxed paces. This basic need for deliberately moderated and human-speed experiences better tuned to the way that people make and understand meaning is the origin of the Slow Food movement.

Naturally, there’s room for a virtual analog of slow food. I’m calling this kind of mediated experience that flows at a kinder, gentler pace “slow media”. Dawdlr, “a global community of friends and strangers answering one simple question: what are you doing, you know, more generally?” is a good example.

Assembled one postcard at a time, Dawdlr exemplifies the collective form of Slow Media, one you can contribute to by creating some content using a standard interface and then submitting it for publication, as long as it carried the proper postage. The paper blog – now updated and known as papercast – might be a precursor.

What are some other examples of Slow Media? Back in January of 2007, AdBusters asked, “Isn’t it time to slow down?” during their national slowdown week.

Slow food has a website, annual gatherings, publications, a manifesto, even a mascot / icon – the snail of course. What’s next for slow media? Maybe a slow wiki, made up of image-mapped screen shots of chalkboards with writing?

Comment » | Customer Experiences, Ideas, Objets Trouves, The Media Environment, User Experience (UX)

May 7th, 2007 — 12:00am

Direct connections between the war in Iraq and the realm of user experience are rare, so I was surprised when one popped up today in an article by the New York Times, titled 2 Car Bombings in Iraq Kill 25.

The article quotes an Iraqi, reacting to the destruction of a house containing a cache of munitions by American soldiers. “The Americans are lying,” said Ali Jabbar, 28, one of several men digging through the rubble, where bicycle handlebars could be seen poking out. “If there were weapons there, they should have taken pictures to prove it.” But in a sign of the challenge Americans face here, Mr. Jabbar said that even if he saw such pictures, he would not be convinced that the destruction was justified. “The Americans can make it up with Photoshop,” he said.

It’s simultaneously terrible and fascinating that a tool I use regularly would appear in this sort of context. And yet it’s not unreasonable, given the ways that many futurists envision and describe warfare centered on information.

Here’s Alvin Toffler, from How will future wars be fought?

Above all, the full implications of what we termed Third Wave “knowledge warfare” have not yet been digested – even in the United States. The wars of the future will increasingly be prevented, won or lost based on information superiority and dominance. And that isn’t just a matter of taking out the other guy’s radar. It means waging the kind of full-scale cyber-war we described in War and Anti-War. Cyber-war involves everything from strategic deception and perception management down to tactical disruption of an adversary’s information systems. It also means understanding the role played by the global media in any conflict today. It means enhancing all your knowledge assets from intelligence, to research and development, training, and communication.

Comment » | The Media Environment, Tools, User Experience (UX)

January 10th, 2006 — 12:00am

egosurf: vi.

“To search the net for your name or links to your web pages. Perhaps connected to long-established SF-fan slang egoscan, to search for one’s name in a fanzine.”

Now a consumable service at: egosurf.org

From the about page:

“egoSurf helps massage the web publishers ego, and thereby maintain the cool equilibrium of the net itself.”

Related posts:

Comment » | The Media Environment

January 10th, 2006 — 12:00am

What happens when this classic vernacular interjection meets linguistics, data visualization, and the Web?

The Aargh page, of course. (It should really be The Aargh! Page, but this is so fantastic that I can’t complain…)

Here’s a screenshot of the graph that shows frequency of variant spellings for aargh in Google, along two axes:

Note the snazzy mouseover effect, which I’ll zoom here:

Looking into the origins aargh inevitably brings up Robert Newton, the actor who played Long John Silver in several Disney productions based on the writings of Robert Louis Stevenson. I remember seeing the movies as a child, without knowing that they were the first live action Disney movies broadcast on television. So do plenty of other people who’ve created tribute pages>.

Aargh may have many spelling variations, but at least three of them bear a stamp of legitimacy, as the editorial review of The Official Scrabble Players Dictionary (Paperback) at Amazon.com explains, “If you’re using the 1991 edition or the 1978 original, you’re woefully behind the Scrabble-playing times. With more than 100,000 2- to 8-letter words, there are some interesting additions (“aargh,” “aarrgh,” and “aarrghh” are all legitimate now), while words they consider offensive are no longer kosher. “

There’s even International Talk Like A Pirate Day, celebrated on September 19th every year. The organizers’ site offers a nifty English-to-Pirate-Translator.

Most random perhaps is the Wikipedia link for Aargh the videogame, from the 80’s, without pirates.

Related posts:

Comment » | The Media Environment

December 15th, 2005 — 12:00am

We rely on many ways of recognizing people, near at hand or from afar; faces, voices, walks, and even the scents from favorite colognes or perfumes help us greet friends, engage colleagues, and identify strangers.

I was in high school when I first noticed that everyone’s key chain made a distinct sound, one that served as a kind of audible calling card that could help recognize people. I started to try to guess who was walking to the front door by learning the unique combinations of sounds — clinking and tinkling from metal keys, rattling and rubbing from ceramic and plastic tokens, and a myriad of other noises from the incredible miscellany people attach to their key rings and carry around with them through life — that announced each of my visitors friends. With a little practice, I could pick out the ten or fifteen people I spent the most time with based on listening to the sounds of key chains. Everyone else was someone I didn’t see often, which was a fine distinction to draw between when gauging how to answer the door.

There are many other audible cues to identity — from the closing of a car door, to the sound of foot steps, or cell phone ring tones — but the key chain is unique because it includes so many different elements: the number and size and materials of the keys, or the layering of different key rings and souveniers people attach to them. A key chain is a sort of impromptu ensemble of found instruments playing little bursts of free jazz like personalized fanfares for modern living.

The sound of someone’s key chain also changes over time, as they add or remove things, or rearrange them. That sound can even change in step with the way your relationship to that person changes. For example, if they buy a souvenier with you and put it on their keychain; or if you give them keys to your apartment. Each of these changes reflects shared experiences, and you can hear the difference in sound from one day to the next if you listen carefully.

And like those other ways of recognizing people I mentioned earlier, which all reach the level of being called signatures when they become truly distinctive, the sound of someone’s key chain serves a sort of audible signature.

Until now, the sound of a keychain was perhaps the only truly unique audible signature that was not part of our person to begin with (like the voice). Now that Jason Freeman has created the iTunes Signature Maker, we may have an audible signaure suitable for the digital realm. The iTunes Signature Maker scans your iTunes library, taking one or two second snippets of many files, and mixing these found bits of sound together into a short audio signature. You choose from a few parameters such as play count, total number of songs, and whether to include videos, and the signature maker produces a .WAV file.

I made an iTunes signature using Jason’s tool a few days ago. I’ve listened to it a few times. It certainly includes quite a few songs I’ve listened to often and can recognize from just a one-second snippet. Calligraphers and graphologists make much of a few handwritten letters on a page: music can say a great deal about someone’s moods, outlook, tastes, or even what moves their soul. I listen to a lot of music via radio, CD’s and even live that isn’t included in this. I’m not sure it represents me. I think it’s up to everyone else to decide that.

But what can you do with one? It’s not practical yet to attach it to email messages, like a conventional .sig. It might be a good way to bookend the mixes I make for friends and family. I can see having a lot of fun listening to a bunch of anonymous iTunes signatures from your friends to try and guess which one belongs to whom. There’s real potential for a useful but non-exhaustive answer to the inevitable question, “What kind of music do you like?” when you meet someone new. Along those lines, Jason may have kicked off a new fad in Internet dating; this is the perfect example of a unique token that can compress a great deal of meaning into a small (digital) package that doesn’t require meeting or talking to exchange. I can see the iTunes signature becoming a speed-dating requisite; bring your iTunes signature file with you on a flash drive or iPod shuffle, and listen or exchange as necessary.

At least the name is easy: what else would you call this besides a “musig”. Maybe an “iSig” or a “tunesig”.

Unique ring tones, door chimes, and start-up sounds are only the beginning. Combine musigs with the music genome project, and you could upload your signature to a clearinghouse online, and have it automatically compared for matches against other people’s musigs based on patterns and preferences. Have it find someone who likes reggae-influenced waltzes, or fado, or who listens to at least ten of the same artists you enjoy. Build a catalog of one musig every month for a year, and ask the engine to describe the change in your tastes. Add a musig to your Amazon wishlists for gift-giving, or even ask it to predict what you might like based on the songs in the file.

You can download my musig / iSig / tunesig / iTunes signature here; note that it’s nearly 8mb.

I’ll think I’ll try it again in a few months, to see how it changes.

No related posts.

Comment » | The Media Environment

November 4th, 2005 — 12:00am

A few months ago, I put up a posting on Mental Models Lotus Notes, and Resililence. It focused on my chronic inability to learn how not to send email with Lous Notes. I posted about Notes, but what led me to explore resilience in the context of mental models was the surprising lack of acknowledgement of the scale of hurricane Katrina I came across at the time. For example, the day the levees failed, the front page of the New York Times digital edition carried a gigantic headline saying ‘Levees Fail! New Orleans floods!’. And yet no one in the office at the time even mentioned what happened.

My conclusion was that people were simply unable to accept the idea that a major metropolitan area in the U.S. could possibly be the setting for such a tragedy, and so they refused to absorb it – because it didn’t fit in with their mental models for how the world works. Today, I came across a Resilience Science posting titled New Orleans and Disaster Sociology that supports this line of thinking, while it discusses some of the interesting ways that semantics and mental models come into play in relation to disasters.

Quoting extensively from an article in The Chronicle of Higher Education titled Disaster Sociologists Study What Went Wrong in the Response to the Hurricanes, but Will Policy Makers Listen? the posting calls out how narrow slices of media coverage driven by blurred semantic and contextual understandings, inaccurately frame social responses to disaster situations in terms of group panic and the implied breakdown of order and society.

“The false idea of postdisaster panic grows partly from simple semantic confusion, said Michael K. Lindell, a psychologist who directs the Hazard Reduction and Recovery Center at Texas A&M University at College Station. ‘A reporter will stick a microphone in someone’s face and ask, ‘Well, what did you do when the explosion went off?’ And the person will answer, ‘I panicked.’ And then they’ll proceed to describe a very logical, rational action in which they protected themselves and looked out for people around them. What they mean by ‘panic’ is just ‘I got very frightened.’ But when you say ‘I panicked,’ it reinforces this idea that there’s a thin veneer of civilization, which vanishes after a disaster, and that you need outside authorities and the military to restore order. But really, people usually do very well for themselves, thank you.’

Mental models come into play when the article goes on to talk about the ways that the emergency management agencies are organized and structured, and how they approach and understand situations by default. With the new Homeland Security paradigm, all incidents require command and control approaches that assume a dedicated and intelligent enemy – obviously not the way to manage a hurricane response.

“Mr. Lindell, of Texas A&M, agreed, saying he feared that policy makers in Washington had taken the wrong lessons from Katrina. The employees of the Department of Homeland Security, he said, ‘are mostly drawn from the Department of Defense, the Department of Justice, and from police departments. They’re firmly committed to a command-and-control model.’ (Just a few days ago, President Bush may have pushed the process one step further: He suggested that the Department of Defense take control of relief efforts after major natural disasters.)

“The habits of mind cultivated by military and law-enforcement personnel have their virtues, Mr. Lindell said, but they don’t always fit disaster situations. ‘They come from organizations where they’re dealing with an intelligent adversary. So they want to keep information secret; ‘it’s only shared on a need-to-know basis. But emergency managers and medical personnel want information shared as widely as possible because they have to rely on persuasion to get people to cooperate. The problem with putting FEMA into the Department of Homeland Security is that it’s like an organ transplant. What we’ve seen over the past four years is basically organ rejection.’

If I read this correctly, misaligned organizational cultures lie at the bottom of the whole problem. I’m still curious about the connections between an organization’s culture, and the mental models that individuals use. Can a group have a collective mental model?

Accoridng to Collective Mental State and Individual Agency: Qualitative Factors in Social Science Explanation it’s possible, and in fact the whole idea of this collective mental state is a black hole as far as qualitative social research and understanding are concerned.

Related posts:

Comment » | Modeling, The Media Environment

November 3rd, 2005 — 12:00am

Apparently, if you wait long enough, all circles close themselves. Case in point: I’ve always thought Golding’s Lord of the Flies nicely captures several of the less appetizing aspects of the typical american junior high school experience.

And I’ve always thought that much of the reality television programming that was all the rage for a while and now seems to be passing like a Japanese fad, is simply a chance for people on all sides of the screen to revisit their own junior high school experiences once again — albeit with a full complement of adult secondary sexual characteristics. When I do channel surf past the latest incarnation of the primal vote-the-jerk-off-the-island epic, Golding’s book always comes to mind.

Then a friend recommended Koushun Takami’s Battle Royale as recreational reading. Battle Royale is, as Tom Waits says, ‘big in Japan’ – it being a Japanese treatment of some of the same themes that drive Lord of the Flies.

The editorial review from Amazon reads:

“As part of a ruthless program by the totalitarian government, ninth-grade students are taken to a small isolated island with a map, food, and various weapons. Forced to wear special collars that explode when they break a rule, they must fight each other for three days until only one “winner” remains. The elimination contest becomes the ultimate in must-see reality television.”

And so the circle closes…

Related posts:

Comment » | Reading Room, The Media Environment

September 17th, 2005 — 12:00am

A tip o’ the hat to Richard Boakes for foiling a second-rate spammer by buying up the domain they were promoting with comment spam before they did.

Related posts:

Comment » | The Media Environment

July 7th, 2005 — 12:00am

I went to the 4th of July concert on the Esplanade this past Monday, for the first time in several years, expecting to show some international visitors genuine Boston Americana. After all, 4th of July celebrations are singularly American experiences; part summer solstice rite, part brash revolutionary gesture, part demonstration of martial prowess, part razzle-dazzle spectacle as only Americans put on.

I suppose a unique American experience is what we got: in return for our trouble, we felt like unpaid extras in a television production recreating the holiday celebrations for a remote viewing audience miles or years away. It was — de-centered — hollow and inverted. It’s become a simulacrum, with a highly unnatural flow driven by the calculus of supra-local television programming goals. The center of gravity is now a national television audience sitting in living rooms everywhere and nowhere else, and not the 500,000 people gathered around the Hatch Shell who create the celebration and make it possible by coming together every year.

Despite all the razzle-dazzle — and in true American fashion there was a lot, from fighter jets to fireworks, via brass bands, orchestras, and pop stars along the way — the experience itself was deeply unsatisfying, because it was obvious from the beginning that the production company (B4) held the interests of broadcasters far more important than the people who come to the Esplanade.

There were regular commercial breaks.

In a 4th of July concert.

For half a million people.

Commercial breaks which the organizers — no doubt trapped between the Scylla of contractual obligations and the Charybdis of shame at jilting a half-million people out of a summer holiday to come to this show — filled with filler. While the commercials aired, and the audience waited, the ‘programmers’ plugged the holes in the concert schedule with an awkward mix of live songs lasting less than three minutes, pre-recorded music, and inane commentary from local talking heads. We felt like we were sitting *behind* a monitor at a taping session for a 4th of July show, listening while other people watched the screen in front.

I bring this out because it offers good lessons for those who design or create experiences, or depend upon the design or creation of quality experiences.

Briefly, those lessons are:

1. If you have an established audience, and you want or need to engage a new one, make sure you don’t leave your loyal customers behind by making it obvious that they are less important to you than your new audience.

2. If you’re entering a new medium, and your experience will not translate directly to the new channel (and which well-crafted experience does translate exactly?), make sure you don’t damage the experience of the original channel while you’re translating to the new one.

3. When adding a new or additional channel for delivering your experience, don’t trade quality in the original channel for capability in the new channel. Many separate factors affect judgments of quality. Capability in one channel is not equivalent to quality in another. Quality is much harder to achieve.

4. Always preserve quality, because consistent quality wins loyalty, which is worth much more in the long run. Consistent quality differentiates you, and encourages customers to recommend you to other people with confidence, and allows other to become your advocates, or even your partners. For advocates, think of all the people who clear obstacles for you without direct benefit, such as permit and license boards. For partners, think of all the people who’s business connect to or depend upon your experience in some way; the concessions vendors who purchase a vending license to sell food and beverages every year are a good example of this.

For people planning to attend next year’s 4th of July production, I hope the experience you have in 2006 reflects some of these lessons. If not, then I can see the headline already, in bold 42 point letter type, “Audiences nowhere commemorate Independence Day again via television! 500,000 bored extras make celebration look real for remote viewers!“

Since this is the second time I’ve had this experience, I’ve changed my judgment on the quality of the production, and I won’t be there: I attended in 2002, and had exactly the same experience.

No related posts.

Comment » | The Media Environment, User Experience (UX)

April 25th, 2005 — 12:00am

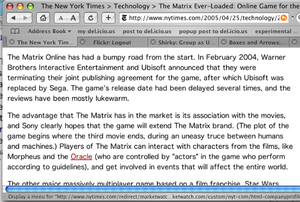

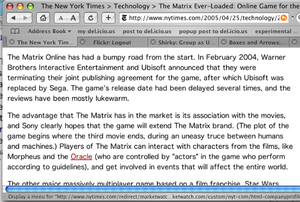

Reading the online edition of the New York Times just before leaving work this afternoon, I came across an ironic mistake that shows the utility of a well developed semantic framework that models the terms and relationships in defingin different editorial contexts. In an article discussing the Matrix Online multiplayer game, text identifying the movie character the Oracle mistakenly linked to a business profile page on the company of the same name. In keeping with the movie’s sinister depictions of technology as a tool for creating deceptive mediated realities, by the time I’d driven home and made mojitos for my visiting in-laws, the mistake was corrected…

Ironic humor aside, it’s unlikely that NYTimes Digital editors intended to confuse a movie character with a giant software company. It’s possible that the NYTimes Digital publishing platform uses some form of semantic framework to oversee automated linking of terms that exist in one or more defined ontologies, in which case this mistake implies some form of mis-categorization at the article level,invokgin the wrong ontology. Or perhaps this is an example of an instance where a name in the real world exists simultaneously in two very different contexts, and there is no semantic rule to govern how the system handles reconciliation of conflicts or invocation of manual intervention in cases when life refuses to fit neatly into a set of ontologies. That’s a design failure in the governance components of the semantic framework itself.

It’s more likely that the publishing platform automatically searches for company names in articles due for publication, and then creates links to the corresponding profile information page without reference to a semantic framework that employs contextual models to discriminate between ambiguous or conflicting term usage. For a major content creator and distributor like the NY Times, that’s a strategic oversight.

In this screen capture, you can see the first version of the article text, with the link to the Oracle page clearly visible:

Mistake:

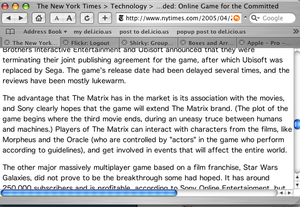

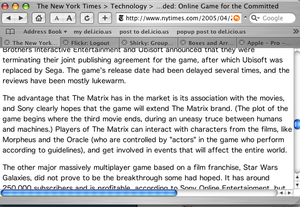

The new version, without the mistaken link, is visible in this screen capture:

New Version:

Related posts:

Comment » | Semantic Web