The EuroHCIR organizers have published proceedings from this year’s workshop (which I was unfortunately unable to attend), which means I can make our paper A Taxonomy of Enterprise Search and Discovery directly available. The complete proceedings are here, and are also packaged as a single download.

Here’s the text of the published paper, including references, and adding in a few illustrations omitted to meet page limits on papers. Many thanks go to co-authors Tony Russell-Rose and Mark Burrell for putting this paper together.

A Taxonomy of Enterprise Search

ABSTRACT

Classic IR (information retrieval) is predicated on the notion of users searching for information in order to satisfy a particular “information need”. However, it is now accepted that much of what we recognize as search behaviour is often not informational per se. For example, Broder (2002) has shown that the need underlying a given web search could in fact be navigational (e.g. to find a particular site or known item) or transactional (e.g. to find a sites through which the user can transact, e.g. through online shopping, social media, etc.). Similarly, Rose & Levinson (2004) have identified consumption of online resources as a further category of search behaviour and query intent.

In this paper, we extend this work to the enterprise context, examining the needs and behaviours of individuals across a range of search and discovery scenarios within various types of enterprise. We present an initial taxonomy of “discovery modes”, and discuss some initial implications for the design of more effective search and discovery platforms and tools.

Categories and Subject Descriptors

H.3.3 [Information Search and Retrieval]: Search process;

H.3.5 [Online Information Services]: Web-based services

General Terms

Human Factors.

Keywords

Enterprise search, information seeking, user behaviour, knowledge workers, search modes, information discovery, user experience design.

1. INTRODUCTION

To design better search and discovery experiences we must understand the complexities of the human-information seeking process. Numerous theoretical frameworks have been proposed to characterize this complex process, notably the standard model (Sutcliffe & Ennis 1998), the cognitive model (Norman 1998) and the dynamic model (Bates, 1989). In addition, others have investigated search as a strategic process, examining the various problem solving strategies and tactics that information seekers employ over extended periods of time (e.g. Kuhlthau, 1991).

In this paper, we examine the needs and behaviours of varied individuals across a range of search and discovery scenarios within various types of enterprise. These are based on an analysis of the scenarios derived from numerous engagements involving the development of search and business intelligence solutions utilizing the Endeca Latitude software platform. In so doing, we extend the classic IR concept of information-seeking to a broader notion of discovery-oriented problem solving, accommodating the much wider range of behaviours required to fulfil the typical goals and objectives of enterprise knowledge workers.

Our approach to enterprise discovery is an activity-centred model inspired by Don Norman’s Activity Centred Design, which “organizes according to usage” whereas “…traditional human centred design organizes according to topic, in isolation, outside the context of real, everyday use.” (Norman 2006). This approach is an extension of previous activity-centred modelling efforts which focused on a “captur[ing] a systematic and holistic view of what users need to accomplish when undertaking information retrieval tasks more complex than searching” (Lamantia 2006), employing Grounded Theory to provide methodological structure (Glaser 1967).

In this context, we present an alternative model focused on information discovery rather than information seeking per se, which has at its core an initial taxonomy of the “modes of discovery” that knowledge workers employ to satisfy their information search and discovery goals. We then discuss some initial implications of this model for the design of more effective search and discovery platforms and tools.

2. INFORMATION RETRIEVAL MODELS

The classic model of IR assumes an interaction cycle consisting of four main activities: the identification an information need, the specification of an appropriate query, the examination of retrieval results, and reformulation (where necessary) of the original query. This cycle is then repeated until a suitable result set is found (Salton 1989).

In both the above models, the user’s information need is assumed to be static. However, it is now acknowledged that information seekers’ needs often change as they interact with a search system. In recognition of this, alternative models of information seeking have been proposed. For example, Bates (1989) proposed the dynamic “berry-picking” model of information seeking, in which the information need (and consequently the query) changes throughout the search process This model also recognises that information needs are not satisfied by a single, final result set, but by the aggregation of results, insights and interactions along the way.

Bates’ work is particularly interesting as it explores the connections between the dynamic model and the search strategies and tactics that professional information-seekers employ. In particular, Bates identifies a set of 29 individual tactics, organised into four broad categories (Bates, 1979). Likewise, O’Day & Jeffries (1993) examined the use of information search results by clients of professional information intermediaries and identified three distinct “search modes” or major categories of search behaviour: (1) Monitoring a known topic or set of variables over time; (2) Following a specific plan for information gathering; (3) Exploring a topic in an undirected fashion.

O’Day and Jeffries also observed that a given search would often evolve over time into a series of interconnected searches, delimited by certain triggers and stop conditions that indicate the transitions between modes or individual searches executed as part of an overall enquiry or scenario. Moreover, O’Day & Jeffries also attempted to characterise the analysis techniques employed by the clients in interpreting the search results, identifying the following six primary categories: (1) Looking for trends or correlations; (2) Making comparisons; (3) Experimenting with different aggregations/scaling; (4) Identifying critical subsets; (5) Making assessments; (6) Interpreting data to find meaning.

More recent investigations into the relationship between information needs and search activities include that of Marchionini (2005), who identifies three major categories of search activity, namely “Lookup”, “Learn” and “Investigate”.

3. A TAXONOMY OF ENTERPRISE SEACH AND DISCOVERY

The primary source of data in this study is a set of user scenarios captured during numerous engagements involving the development of search and business intelligence solutions utilizing the Endeca Latitude software platform. These scenarios take the form of a simple narrative that illustrates the user’s end goal and the primary task or action they take to complete it, followed by a brief description of their job function or role, for example:

“I need to understand a portfolio’s exposures to assess portfolio-level investment mix” (Portfolio Manager)

“I need to understand the quality performance of a part and module set in manufacturing and the field so that I can determine if I should replace that part” (Engineering)

These scenarios were manually analyzed to identify themes or modes that appeared consistently throughout the set. For example, in each of the scenarios above there is an articulation of the need to develop an understanding or comprehension of some aspect of the data, implying that “comprehending” may constitute one such discovery mode. Inevitably, this analysis process was somewhat iterative and subjective, echoing the observations made by Bates (1979) in the identification of her search tactics: “While our goal over the long term may be a parsimonious few, highly effective tactics, our goal in the short term should be to uncover as many as we can, as being of potential assistance. Then we can test the tactics and select the good ones. If we go for closure too soon, i.e., seek that parsimonious few prematurely, then we may miss some valuable tactics.”

There are however some guiding principles that we can apply to facilitate convergence on a stable set. For example, an ideal set of modes would exhibit properties such as: Consistency (they represent approximately the same level of abstraction); Orthogonality (they operate independently to each other); and Comprehensiveness (they address the full range of discovery scenarios).

The initial set of discovery modes to emerge from this analysis consists of a set of nine, arranged into three top-level categories consistent with those of Marchionini (2005). The nine modes are as follows, each shown with a brief definition:

1. Lookup

1a. Locating: To find a specific (possibly known) item;

1b. Verifying: To confirm or substantiate that an item or set of items meets some specific criterion;

1c. Monitoring: To maintain awareness of the status of an item or data set for purposes of management or control

2. Learn

2a. Comparing: To examine two or more items to identify similarities & differences;

2b. Comprehending: To generate insight by understanding the nature or meaning of an item or data set;

2c. Exploring: To proactively investigate or examine an item or data set for the purpose of serendipitous knowledge discovery

3. Investigate

3a. Analyzing: To critically examine the detail of an item or data set to identify patterns & relationships;

3b. Evaluating: To use judgment to determine the significance or value of an item or data set with respect to a specific benchmark or model

3c. Synthesizing: To generate or communicate insight by integrating diverse inputs to create a novel artefact or composite view

Evidently, the output of this process has been optimized for the current data set and in that respect represents an initial interpretation that will need to evolve further. For example, “monitoring” may appear to be a lookup activity when considered in the context of a simple alert message, but when viewed as a strategic activity performed by an executive in the context of an organisational dashboard, a much greater degree of interaction and complexity is implied. Conversely, “exploring” is a concept whose level of abstraction may prove somewhat higher than the others, thus breaking the consistency principle suggested above.

However, the true value of the modes will be realised not by their conceptual purity or elegance but by their utility as a design resource. In this respect, they should be judged by the extent to which they facilitate the design process in capturing important characteristics common to enterprise search and discovery experiences, whilst flexibly accommodating arbitrary variations in domain, information resources, etc.

4. MODE SEQUENCES AND PATTERNS

A further interesting observation arising from the above analysis is that the mapping between scenarios and modes is not one-to–one. Instead, some scenarios are seen to involve a number of modes, sometimes with a primary or dominant mode, and often with an implied linear sequence. Moreover, certain sequences of modes tend to re-occur more frequently than others, forming specific “mode chains” or patterns, analogous to higher-level syntactic units. These patterns provide a framework for understanding the transitions between modes (echoing the triggers identified by O’Day & Jeffries), and allude to the existence of natural seams that can be used be used to provide further insight into information enterprise search and discovery behaviour.

These mode chains echo the above-mentioned efforts to create goal-based information retrieval models, which yielded modes and a set of broadly applicable “information retrieval patterns that describe the ways users combine and switch modes to meet goals: Each pattern is assembled from combinations of the same four [elemental] modes” (Lamantia 2006).

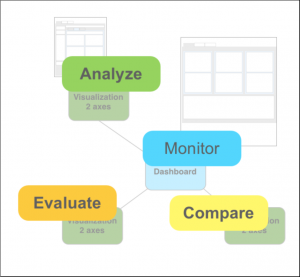

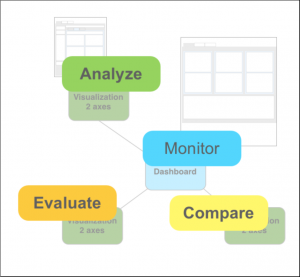

Mode Networks

Figure 1. Discovery mode network

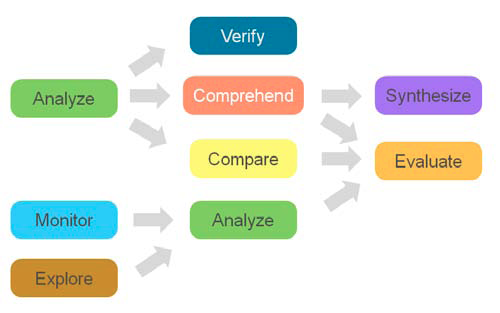

The five most frequent mode patterns are listed below. These have been assigned descriptive (if somewhat informal) labels to aid their characterisation, along with the sequence of modes they represent and an associated example scenario:

- Comparison-driven optimization: (Analyze-Compare- Evaluate) e.g. “Replace a problematic part with an equivalent or better part without compromising quality and cost”

- Exploration-driven optimization: (Explore-Analyze-Evaluate) e.g. “Identify opportunities to optimize use of tooling capacity for my commodity/parts”

- Strategic Insight (Analyze-Comprehend-Evaluate) e.g. “Understand a lead’s underlying positions so that I can assess the quality of the investment opportunity”

- Strategic Oversight (Monitor-Analyze-Evaluate) e.g. “Monitor & assess commodity status against strategy/plan/target”

- Comparison-driven Synthesis (Analyze-Compare-Synthesize) e.g. “Analyze and understand consumer-customer-market trends to inform brand strategy & communications plan”

Further insight may be derived by examining how the mode patterns combine across all the scenarios to the form of a “mode network”, as shown in Figure 1. Evidently, some modes act as “terminal” nodes, i.e. entry points or exit points to a discovery scenario. For example, Monitor and Explore feature only as entry points at the initiation of a scenario, whilst Synthesize and Evaluate feature only as exit points to a scenario.

5. DESIGN PRINCIPLES FOR SEARCH AND DISCOVERY SOLUTIONS

The modes establish a ‘taskonomy’ or collection of defined discovery activities which are structurally consistent, domain and scale independent, orthogonal, semantically distinct, conceptually connected, and flexibly sequenceable. Such a profile — analogous to notes in the musical scale, or the words and phrases we assemble into sentences — should allow the modes to serve as a language for the design of variable scale activity-centered discovery solutions through common constructive mechanisms such as concatenation, combination and nesting. And if the modes do act as an elementary grammar for discovery, then sustained use as a functional and interaction design language should result in the creation of larger and more complex units of meaning which offer cumulative value.

Professional experience with employing the modes as both an analytical framework for understanding discovery needs and as a design grammar for the definition of discovery solutions suggests that both implications are valid. Further, our observations of using the modes suggest the existence of recognizable patterns in the design of discovery solutions. We will briefly discuss some of the patterns observed, doing so at three common levels of solution scale: on the level of a single functional or interface element, for whole screens or interfaces composed of multiple functional elements, and for applications comprising multiple screens.

5.1 Single element patterns

5.1.1 Comparison Views

One of the most common design patterns is to support the need for the Compare mode by creating A/B type comparison views that present two display panes – each containing data display charts or tables; or single items or groups of items – side by side to emphasize similarities and differences.

5.1.2 Contextual Views

Another common design pattern supports the Analysis mode by allowing a fore-grounded view of a single chart, table, item, or list, accompanied by its contextual ‘halo’ – the full body of information available about the element such as status, origin, format, relationships to other elements; annotations; etc.

5.2 Whole screen patterns

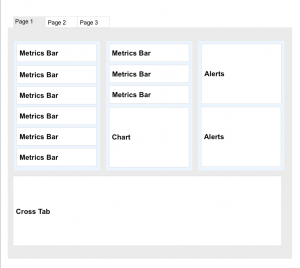

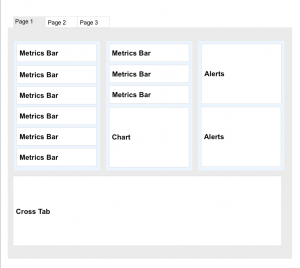

5.2.1 Dashboard

One of the most common screen-level design patterns is to support the Monitoring and Synthesis modes by presenting a collection of metrics which in aggregate provide the status of independent processes, groups, or progress versus goals in a ‘dashboard’ style screen.

Figure: Dashboard Screen

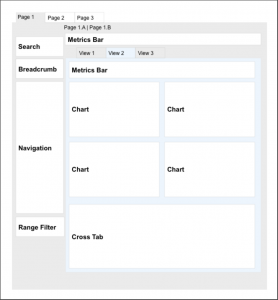

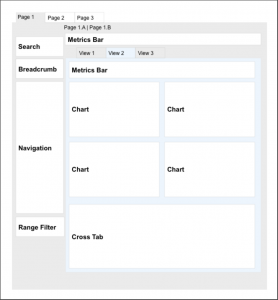

5.2.2 Visual Discovery Screen: 4-Dimensions

A second common screen-level design pattern for discovery experiences is the visual discovery screen, which supports modes such Exploration, Evaluation, and Verification by layering views that present visualizations of several dimensions of a single axis of focus such as a core process, organizational unit, or KPI. When switching between layered views, the axis in focus remains the same, but the data and presentation in the dimensions adjusts to match the preferred discovery mode.

Figure: Visual Analysis Screen

5.3 Application-level patterns

5.3.1 Differentiated Application

The ‘Differentiated Application’ pattern assembles a collection of individual screens whose distinct compositions and designs support individual discovery modes of Analysis, Comparison, Evaluation and Monitoring in aggregate to address the ‘Strategic Oversight’ mode sequence. Application-level patterns often address a spectrum of discovery needs for a group of users with differing organizational responsibilities, such as management vs. detailed analysis.

Figure: Differentiated Application Structure

6. DISCUSSION

The above analysis is predicated on the notion that the user scenarios provide a unique insight into the information needs of enterprise knowledge workers. However, a number of caveats apply to both the data and the approach.

Firstly, the scenarios were originally generated to support the development of a specific implementation rather than for the analysis above. Therefore, the principles governing their creation may not faithfully reflect the true distribution or priority of information needs among the various end user populations. Secondly, the particular sample we selected for this study was based on a number of pragmatic factors (including availability), which may not faithfully represent the true distribution or priority among enterprise organizations. Thirdly, the data will inevitably contain some degree of subjectivity, particularly in cases where scenarios were generated by proxy rather than with direct end-user contact. Fourthly, the data will inevitably contain some degree of inconsistency in cases where scenarios were documented by different individuals.

We should also acknowledge a number of caveats concerning the process itself. In inductive work with foundations in qualitatively centered frameworks such as Grounded Theory, it is expected that a number of iterations of a “propose-classify-refine” cycle will be required for the process to converge on a stable output (e.g. Rose & Levinson, 2004). In addition, those iterations should involve a variety of critical viewpoints, with the output tested and refined using a separate, independent sample on each iteration. Likewise, the process by which scenarios are classified would benefit from further rigour: this is a critical part of the process and of course relies on human judgement and inference, but that judgement needs to go beyond simple word matching and be consistently applied to each scenario so that subtle distinctions in meaning and intent can be accurately identified and recorded.

That said, some interesting comparisons can already be made with the existing frameworks. For example, the first and third of the search modes suggested by O’Day and Jeffries have also been identified as distinct discovery modes in our own study, and the second (arguably) maps on to one or more of the mode chains identified above. Likewise, the search results analysis techniques that O’Day & Jeffries identified also present some interesting parallels.

7. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

To design better search and discovery experiences we must understand the complexities of the human-information seeking process. In this paper, we have examined the needs and behaviours of varied individuals across a range of search and discovery scenarios within various types of enterprise. In so doing, we have extended the classic IR concept of information-seeking to a broader notion of discovery-oriented problem solving, accommodating the much wider range of behaviours required to fulfil the typical goals and objectives of enterprise knowledge workers.

In addition, we have proposed an alternative model focused on information discovery rather than information seeking which has at its core a taxonomy of “modes of discovery” that knowledge workers employ to satisfy their information search and discovery goals. We have also examined some of the initial implications of this model for the design of more effective search and discovery platforms and tools.

Suggestions for future work include further iterations on the “propose-classify-refine” cycle using independent data. This data should ideally be acquired based on a principled sampling strategy that attempts where possible to address any biases introduced in the creation of the original scenarios. In addition, this process should be complemented by empirical research and observation of knowledge workers in context to validate and refine the discovery modes and triggers that give rise to the observed patterns of usage.

8. REFERENCES

[1] Bates, Marcia J. 1979. “Information Search Tactics.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science 30: 205-214

[2] Bates, Marcia J. 1989. “The Design of Browsing and Berrypicking Techniques for the Online Search Interface.” Online Review 13: 407-424.

[3] Broder, A. 2002. A taxonomy of web search, ACM SIGIR Forum, v.36 n.2, Fall 2002

[4] Kuhlthau, C. C. 1991. Inside the information search process: Information seeking from the user’s perspective. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42, 361-371.

[5] Lamantia, J. 2006. “10 Information Retrieval Patterns” JoeLamantia.com, /information-architecture/10-information-retrieval-patterns

[6] Glaser, B. & Strauss, A. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

[7] Marchionini, G. 2006. Exploratory search: from finding to understanding. Commun. ACM 49(4): 41-46

[8] Norman, Donald A. 1988. The psychology of everyday things. New York, NY, US: Basic Books.

[9] Donald A. Norman. 2006. Logic versus usage: the case for activity centered design. Interactions 13, 6

[10] O’Day, V. and Jeffries, R. 1993. Orienteering in an information landscape: how information seekers get from here to there. INTERCHI 1993: 438-445

[11] Rose, D. and Levinson, D. 2004. Understanding user goals in web search, Proceedings of the 13th international conference on World Wide Web, New York, NY, USA

[12] Salton, G. (1989). Automatic Text Processing: The Transformation, Analysis, and Retrieval of Information by Computer. Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA.

[13] A.G. Sutcliffe and M. Ennis. Towards a cognitive theory of information retrieval. Interacting with Computers, 10:321–351, 1998.