For me, the cumulative contextual gap became too great to bridge. The intensity of so many new things made my own substituted context insufficient to maintain the texture of meaning in my home – one of the most personal and significant of settings.

The IKEA Brand

A well-developed brand evokes specific emotional resonances, and does so consistently with each customer’s experiences. Brand designers and marketers carefully choose emotions based on the personality the brand should establish, and the business goals behind it. Brands often try to create connections to the deeply rooted psycho-personal concepts and constructs that shape our basic ways of thinking and feeling. Brands attempt to become associated with “identity“, “lifestyle“, or in the case of IKEA, “home”. The IKEA brand is built on associations with cost-consciousnes s, design sensibility, unconventionality, and ecological awareness. Showcased in the IKEA products furnishing one’s home, these associations are meant to serve as evidence of an outlook and set of priorities for life in general.

Ambition is one thing, and success quite another. Yet by all measures, IKEA’s brand is successful: in addition to superb sales and profitability (secured by the arcane corporate structures that shield IKEA from taxation), it commands tremendous customer loyalty, and inspires irrational behavior that borders on blindly devoted. I create funny stories about the meanings of product names to ease the mysteries of their origins. But other seasoned American retail customers like Roger Penguino and Stacy Powell camp in front of about-to-open IKEA stores for weeks in order to win prizes of modest value.

When Roger Penguino heard Ikea was offering $4,000 in gift certificates to the first person in line at the opening of its new Atlanta store, he had no choice. He threw a tent in the back of his car and sped down to the site. There, the 24-year-old Mac specialist with Apple Computer Inc. (AAPL ) pitched camp, hunkered down, and waited. And waited. Seven broiling days later, by the time the store opened on June 29, more than 2,000 Ikea fanatics had joined him.

From Ikea: How the Swedish Retailer became a global cult brand

The Flat-pack Religion: Mysterious Faith

Penguino’s behavior is unusual by normal standards, perhaps even fanatical, but not unique among IKEA customers.

Christy Powell, 48, camped out for eight nights before the opening of a new Ikea store on Interstate 10 at Antoine in Houston, Texas. Her quest to claim a US$ 10,000 prize meant she sat through sizzling heat, a violent thunderstorm and the din of builders finishing the car park. By the day of the opening, the queue behind Powell had swelled to 700. After a 192-hour wait, she bought just 12 plates and bowls for $18 plus tax.

From Is IKEA For Everyone?

Powell and Penguino’s stories make the IKEA brand’s capacity to inspire people clear. Inspiration is a rare achievement for many religions, let alone a consumer brand. Inspired religious believers test their faith(s) in ways often incomprehensible and certainly too numerous to count. At heart all these demonstrations address the same goal of affirming the consistency of a system of beliefs through personal experience. Like the pilgrim who travels from afar and waits in penitential devotion for entry to a temple or sacred site, IKEA shoppers endure traffic jams, and long lines (in the parking lot, in the store, in the warehouse, to load purchases into cars…) to pay for the privilege of membership in the global community of IKEA.

Penguino is a citizen of IKEA World, a state of mind that revolves around contemporary design, low prices, wacky promotions, and an enthusiasm that few institutions in or out of business can muster. Perhaps more than any other company in the world, Ikea has become a curator of people’s lifestyles, if not their lives. At a time when consumers face so many choices for everything they buy, Ikea provides a one-stop sanctuary for coolness. It is a trusted safe zone that people can enter and immediately be part of a like-minded cost/design/environmentally-sensitive global tribe. There are other would-be curators around — Starbucks and Virgin do a good job — but Ikea does it best.

From Ikea: How The Swedish Retailer Became a Global Cult Brand

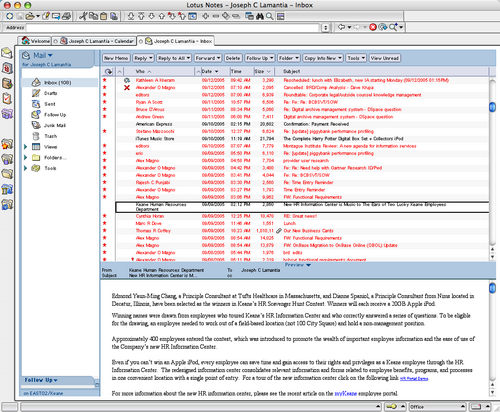

However well IKEA may understand my lifestyle – or at least the set of products that might fit into my lifestyle and home furnishing needs – my experiences of disorientation and a sense of being confronted with the alien within an intimate setting are not the sorts of emotions customarily attached to a successful brand. To dispel part of the mystery of this persistent discontinuity, I set off to find out more about where my new Swedish friends came from: It’s a secretive place, full of interconnected and opaque systems.

A World of Systems

Many religions combine elements of mystery and the inexplicable with high levels of systematicity (a particular recipe the discipline of comparative religion works to understand and articulate). In the same way that brands can parallel religions in their capacity to inspire non-rational behavior, brands parallel religions by showing characteristics of systems. From a systems perspective, a brand is a larger whole made up of interconnected emotional associations and psychologically charged concepts that customers experience through many moments, spread across diverse channels and environments (online or transactional, advertising, services, packaging, language, etc.). IKEA’s chosen values – ecological awareness, design sensibility, cost-consciousness – combine together to characterize a modern outlook that balances the enjoyment of novelty and design-enhanced consumerism with longer-term goals. In this system, IKEA partisans can have fun, without sacrificing the future – their own or everyone else’s. It’s a solid compromise that demonstrates the classic characteristics of a viable system (more on this shortly).

On closer examination, this sort of systems thinking permeates IKEA’s enterprise at every level, from design, operations, and logistics to it’s financial and legal structures. And it happens on gigantic scales: rather than achieve success in a single category of life accessories, IKEA’s avowed is aim to create a comprehensive range of products for the home (perhaps a totality?), as founder Ingvar Kamprad says explicitly in his tract, ‘The Testament of a Furniture Dealer’.

“The objective must be to encompass the total home environment; that is, to offer furnishings and fittings for every part of the home whether indoors or outdoors … It must reflect our way of thinking by being as simple and straightforward as we are ourselves. It must be durable and easy to live with. It must reflect an easier, more natural and unconstrained way of life”

From IKEA: The Philosophy

To realize Kamprad’s goal of comprehensiveness on the level of the individual customer experience, IKEA presents products within an enveloping physical environment of massive scale and all-embracing completeness, synthesizing a bizarre Sims-style furnitureverse that customers navigate via pre-determined paths wending seemingly at random through an endless fractal conglomeration of minutely detailed, yet wholly contrived, living settings.

What enthralls shoppers and scholars alike is the store visit — a similar experience the world over. The blue-and-yellow buildings average 300,000 square feet in size, about equal to five football fields. The sheer number of items — 7,000, from kitchen cabinets to candlesticks — is a decisive advantage. “Others offer affordable furniture,” says Bryan Roberts, research manager at Planet Retail, a consultancy in London. “But there’s no one else who offers the whole concept in the big shed.” …The furniture itself is arranged in fully accessorized displays, down to the picture frames on the nightstand, to inspire customers and get them to spend more. The settings are so lifelike that one writer is staging a play at Ikea in Renton, Wash.

From Ikea: How The Swedish Retailer Became a Global Cult Brand

Overall, one experiences the IKEA store as a self-guided tour through a hybrid landscape composed of deserted last-man-alive-on-earth-sitcom-sets, and impromptu shanty towns created by unseen populations of refugees fleeing brush wars and guerilla conflicts deep in the interior design, home-decor, and catalog-shopping hinterlands. And like all things IKEA, these settings inspire unusual behavior, such as the guerilla filming of Real World satire skits.

Extractive Architectures

Anyone who’s visited an IKEA store understands the obvious parallels to other well-known architectures of control, such as casinos (also here, including a comment that cites the IKEA parallel, [found while researching this post]) and amusement parks. I call this specific variant an ‘extractive architecture’ since the common objective of these forms designed to separate visitors from the outside world – environmental cues like weather and daylight, or social chronological frames of reference – is to cocoon patrons in a fantastical alternate reality that enhances the amount of time / money / attention the creators can extract from their visitors as they pass through.

The logistics behind the massive IKEA stores also reflect system thinking on truly gigantic scales: the IKEA shopping experience relies on a global network of automated warehouses and distribution centers as large as 180,000 cubic meters in size. In aggregate, these buildings – there are 27 of them – would make the list of largest buildings in the world. Naturally, IKEA exerts control over the infrastructure for this strange realm in the same fastidious fashion.

For Want of A Nail, The Kingdom Was Put On Back Order

Given the effort and attention to detail required to create and supply this all-embracing (and also artificial) context and tune it to an extractive purpose, the uncomfortable and challenging strangeness of IKEA’s product names seems like a discontinuity in the otherwise smooth continuum of the IKEA brand. Or, if IKEA’s product names are not carefully managed – meaning little or no effort goes into choosing them – then the practice of naming products is the one aspect of the IKEA experience not to be thought through and carefully designed from start to finish. Which is a discontinuity at a more fundamental level.

Perhaps the most common form of discontinuity IKEA customers experience is simple lack of product availability.

Ikea owns 27 distribution centres like this across the globe, cavernous warehouses where flatpack boxes make their only stop between supplier and store. The system is designed to operate with mathematical precision to shave away at costs. When a Faktum wardrobe is bought at Brent Park, the cash till registers the purchase; the purchases add up until they trigger a warning that stocks are running low; and the message is passed electronically up the line to the nearest distribution centre, from where more can be dispatched. There is no waste of time, effort, or money. The system is perfect.

Except, of course, that it isn’t – or at least it wasn’t the last time I tried to buy a Lycksele sofabed. Ironically for a company so committed to tolerating mistakes, Ikea appears to have automated Kamprad’s ethic of frugality to such a degree that the tiniest human error now cascades through the system, magnifying itself and sparking havoc. A shopfloor worker at Brent Park forgets to mark down that a box has been damaged and thrown out; the automatic trigger is never sent; a shipment of several hundred boxes remains undispatched from the warehouse – and an angry customer ends up driving back home along London’s North Circular, cursing Ikea bitterly once more.

From The miracle of Älmhult

Discontinuities within comprehensive systems, like tax code loopholes, the backdoor in WOPR’s programming in Wargames or Neo’s special powers in The Matrix, matter because they signal internal inconsistency; and often presage changes in system state from stability to instability. Unstable systems often exhibit low viability, meaning they are not “organized in such a way as to meet the demands of surviving in the changing environment”. In simpler language, discontinuity often signals and leads to failure.

Emotional and experiential systems such as brands rely on very high levels of internal consistency. They must exhibit stability and viability at all levels, and across all touch points, especially the context sensitive areas of vocabulary and naming that form much of the linguistic aspects experience of a brand. Given the sensitivity and significance of cultural context, IKEA’s refusal to translate its product names seems counterproductive. However, persuading – or compelling – people to speak your language in preference to their own is one step toward persuading or compelling them to think from your frame of reference. Evangelists of all varieties know this well, and so does IKEA.

The Ikea path to self-fulfilment is not, really, a matter of choice. “They have subtle techniques for encouraging compliance,” argues Joe Kerr, head of the department of critical and historical studies at the Royal College of Art. “And in following them you become evangelists for Ikea. If you look at [police] interrogation techniques, for example, you see that one of the ways you break somebody’s will is to get them to speak in your language. Once you’ve gone to a shop and asked for an Egg McMuffin, or a skinny grande latte, or a piece of Ikea furniture with a ludicrous name, you’re putty in their hands.”

From The miracle of Älmhult

Still, forcing me to speak a foreign language at random does nothing to convert me to your way of thinking. Like medieval Catholics who recited the liturgy in Latin without comprehending it, I may appear to be a convert to IKEA’s wacky religion by referring to my new Swedish friends using the hard-to-pronounce and impossible-to-spell-properly-with-an-English-keyboard names they inherited from their homeland, when in reality I am merely mouthing the phonemes of a sacrament I do not in the least understand.

With a little research, I discovered there is a system for naming IKEA’s products:

“There is a system,” Maria Vinka, one of Ikea’s 11 in-house product designers, is saying, wedged into an easy chair in Älmhult’s own branch of Ikea, as she attempts to explain the fiendishly complex logic by which the company names its products. “For bathrooms, it’s Norwegian lakes. Kitchens are boys, and bedrooms are girls. For beds, it’s Swedish cities. There’s a lady who sits there and comes up with new names, making sure there isn’t a name that means something really ugly in another language. But it doesn’t always work. We gave a bed a name that means ‘good lay’ in German.”

From The miracle of Älmhult

All of the many systems comprising the IKEA enterprise seem opaque to varying degrees. The ownership structures that channel IKEA’s massive revenues and profits to destinations unknown, and shield the interlinked companies from taxation, regulation, and oversight are especially convoluted, and serve to maintain very low levels of transparency and tight control by Ivar Kamprad and his family.

…Kamprad set about creating a business structure of arcane complexity and secrecy. Today, therefore, The Ikea Group is ultimately owned by the Stichting Ingka Foundation, a charitable trust based in the Netherlands. A separate company, Inter Ikea Systems, owns Ikea’s intellectual property – its concept, its trademark, its product designs. In a labyrinthine arrangement, Inter Ikea Systems then makes franchise deals with The Ikea Group, allowing it to manufacture and sell products. “The big question is who owns Inter Ikea Systems,” says Stellan Björk, a Swedish journalist, who in 1998 wrote a book, never translated into English, detailing the extraordinary opacity of the company’s organisation and the extent of its tax avoidance. The answer to Björk’s question seems to be that no one knows. “It seems to be owned by various foundations and offshore trusts,” Björk says – some based in the Caribbean – “through which the family controls it.” The motivation behind all this mystery, the company insists, “was to prevent Ikea being split up after his [Kamprad’s] death [and] to ensure the long term survival of Ikea and its co-workers.”

From The miracle of Älmhult

And further:

The IKEA trademark and concept is owned by Inter IKEA Systems, another private Dutch company, but not part of the Ingka Holding group. Its parent company is Inter IKEA Holding, registered in Luxembourg. This, in turn, belongs to an identically named company in the Netherlands Antilles, run by a trust company in Curaçao. Although the beneficial owners remain hidden from view–IKEA refuses to identify them–they are almost certain to be members of the Kamprad family.

From IKEA: Flat-pack accounting

A Little Help From My New Swedish Friends

In Part 1 of this essay, I talked about the mysterious context of IKEA product names, how I’d developed a habit of recontextualizing the names of the IKEA products, and ended by noting that after encountering too many at once, the names became a source of discomfort rather than inspiration for whimsical enjoyment.

In this second part, I went looking for some information on IKEA’s product naming practices to bridge this gap. I found out that IKEA chooses names as prosaically as most other household accessories designers shepherding a brand experience for retail consumers; by borrowing from the deep and localized reservoirs of their root culture. I also found a series of interconnected but opaque systems – financial, logistical, philosophical, branding, experiential – that show their own strange form of symmetry and internal consistency.

I’m left feeling a bit like an IKEA shopper who’s completed their first trip through one of the iconic blue and yellow stores, and is now outside, blinking in the sunlight, bemused and a bit puzzled by the comprehensive strangenesses I’ve just encountered, but looking forward to spending some time with my new Swedish friends.

PS: If you’re wondering what the future holds for IKEA consider this:

The Ikea concept has plenty of room to run: The retailer accounts for just 5% to 10% of the furniture market in each country in which it operates. More important, says CEO Anders Dahlvig, is that “awareness of our brand is much bigger than the size of our company.” That’s because Ikea is far more than a furniture merchant. It sells a lifestyle that customers around the world embrace as a signal that they’ve arrived, that they have good taste and recognize value. “If it wasn’t for Ikea,” writes British design magazine Icon, “most people would have no access to affordable contemporary design.” The magazine even voted Ikea founder Ingvar Kamprad the most influential tastemaker in the world today.

From Ikea: How The Swedish Retailer Became a Global Cult Brand

PPS: For reference, IKEA names products in the following fashion:

- Upholstered furniture, coffee tables, rattan furniture, bookshelves, media storage, doorknobs: Swedish place names

- Beds, wardrobes, hall furniture: Norwegian place names

- Dining tables and chairs: Finnish place names

- Bookcase ranges: Occupations

- Bathroom articles: Scandinavian lakes, rivers and bays

- Kitchens: grammatical terms, sometimes also other names

- Chairs, desks: men’s names

- Materials, curtains: women’s names

- Garden furniture: Swedish islands

- Carpets: Danish place names

- Lighting: terms from music, chemistry, meteorology, measures, weights, seasons, months, days, boats, sailors’ language

- Bed linen, bedcovers, pillows/cushions: flowers, plants, precious stones

- Children’s items: mammals, birds, adjectives

- Curtain accessories: mathematical and geometrical terms

- Kitchen utensils (cutlery, crockers, textiles, glass, porcelain, tablecloths, candles, serviettes, decorative articles, vases etc.): foreign words, spices, herbs, fish, mushrooms, fruits or berries, functional descriptions

- Boxes, wall decoration, pictures and frames, clocks: colloquial expressions, also Swedish placenames

Translation from original in German by Margaret Marks